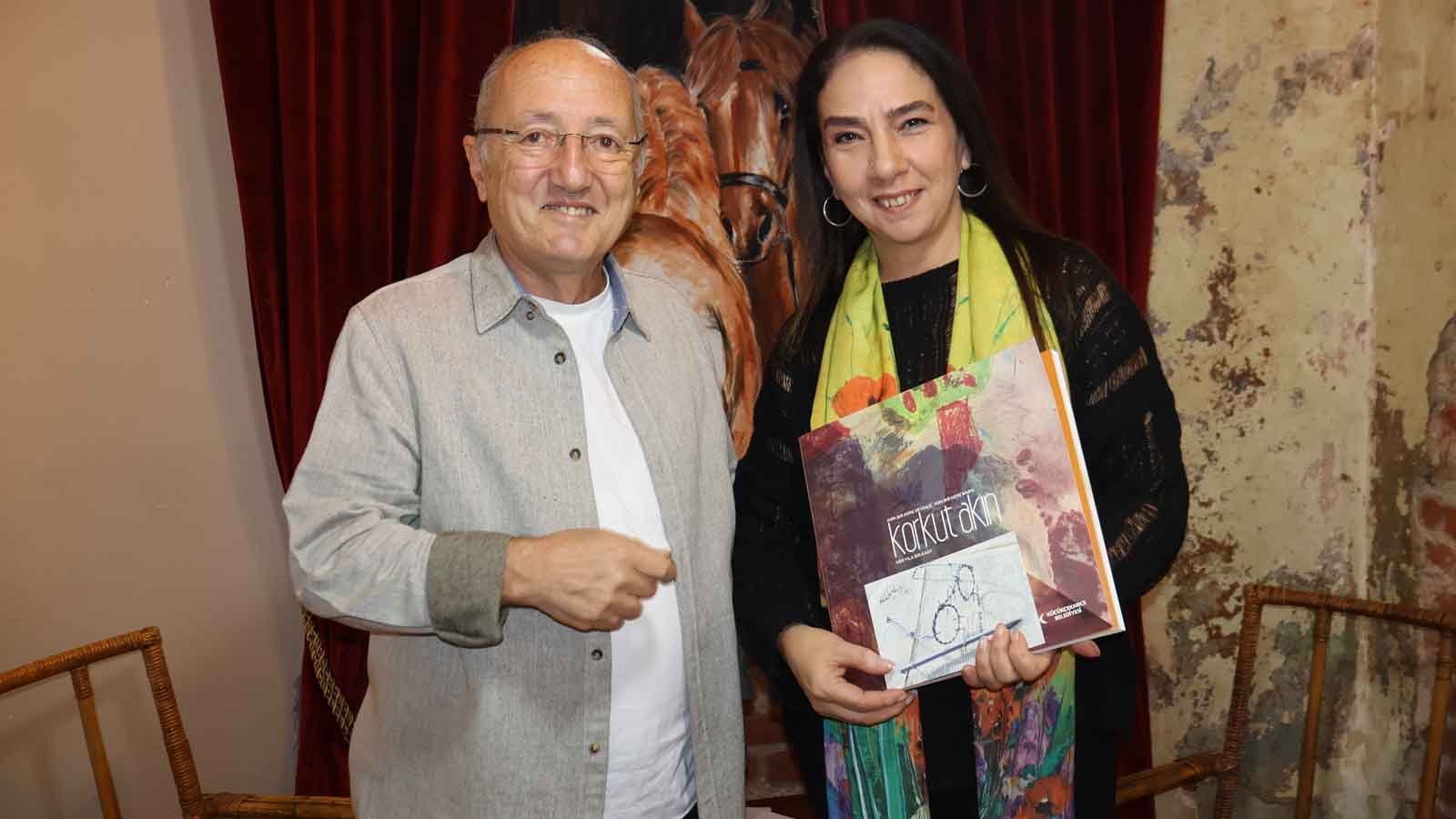

Hosted by Zehra Aksoy, the program “Rengârenk,” which captures the pulse of the cultural and artistic world, welcomed in its fifth episode the veteran painter Muhsin Bilyap, who introduced the unique movement “Alaturkism” with its own manifesto to Turkish painting art. The conversation, in which the artist sincerely shared his 50 years of experience, the roots of his artistic philosophy, and his struggle to create an art language belonging to these lands, was more than just an interview; it was almost like a masterclass.

“I Was Born Inside Painting: Rubens on the Wall, My Mother’s Voice in My Ear”

Muhsin Bilyap shared an impressive memory, explaining that the foundations of his unshakable bond with art were laid even before words: “My mother loved painting very much. When I opened my eyes and began to say mom and dad, there was Rubens on the wall. My mother was teaching me Rubens, Gauguin, İbrahim Safi.” Bilyap described his childhood as “double-lived,” stating that on one hand, he was a child playing with a spinning top in the street, and on the other, a soul living in the magical world of paintings at home. He emphasized that growing up in a family of Russian and Erzurum origins, where Orthodox and Muslim cultures intertwined, was the most fundamental dynamic nurturing the “contrasts and harmonies” in his art. This rich cultural heritage was also the precursor of his approach that brought together East and West, tradition and modernity in his works.

The Birth of Alaturkism: A Manifesto Born from the Phrase “Like Turkish Painting”

The most striking part of the conversation was the story of the birth of the “Alaturkism” movement founded by Bilyap. Expressing his discomfort at being overshadowed throughout his career by Western-centered art movements (surrealism, expressionism, etc.), Bilyap described this as a kind of cultural alienation. “Those who came to my studio in Kadıköy often said, ‘Oh, these are so much like Turkish paintings.’ This made me think,” said the artist, explaining that this phrase led him to name his own artistic language. Bilyap narrated the process as follows: “I began calling what I did Alaturka painting. Because Alaturka was a term that both expressed us and was internationally known thanks to Mozart’s ‘Rondo alla Turca.’ So I named this movement Alaturkism.”

Bilyap emphasized that Alaturkism was not so much a longing for the past, but rather a message for the future and a mission to build a bridge. According to him, there was a fundamental rupture in Turkish painting art: “Our so-called modern painters have lost their ties with tradition. On the other hand, our friends who work traditionally have lost their ties with modernity. However, bringing them together will give birth to a new Turkish art.” In this sense, Alaturkism assumes the responsibility of carrying the rich heritage of this land—from the Seljuks to the Ottomans, from the Hittites to Byzantium—into the future with a modern interpretation.

From Hazelnut Sack to Canvas: The Spirit of Material and the Creative Process

The details the artist shared about his creative process revealed how holistically he approached art. Bilyap pointed out that he especially used “jute canvas,” made from hemp and a material that lives with its unique texture, and even at one point transformed “hazelnut sacks” into canvas. These authentic materials were an essential element feeding the spirit of his works. Defining the beginning of a work with the words, “A work generally begins with an image, a thought, an imagination,” Bilyap underlined that his art avoids didactic narration: “Rather than having my paintings explain something, I want them to evoke something; to evoke a time, a period, a thought.”

Art, Society and Criticism: “The Artist Exists Together with the Audience”

Muhsin Bilyap offered a significant social critique by drawing attention to the lack of an “art life” in Turkey. “In Turkey, there are artists, there are collectors, but there is no art life. There are no channels to make ordinary people love art,” Bilyap said, pointing out that popular culture—from TV series to newspapers—excludes art. Emphasizing the critical role of the audience for the survival of art, he said, “An artist is nothing alone. The audience is not merely one who comes and watches; the greatest force that keeps the artist alive is the audience itself, and this is an inseparable part of art,” thus placing great responsibility on art lovers. At this point, he recalled the late art critic Elif Naci’s criticism, “Our painters went directly to Paris without first entering the Turkish Islamic Art Museum,” and his painting academy professor Leopold Levy’s plea, “Do not imitate the West, there is an incredible treasure in your own geography,” once again proving how deeply and historically Alaturkism responds to a genuine need.

The full version of this profound and inspiring conversation with painter Muhsin Bilyap on art, history, and life awaits art lovers on the Turkey News Portal websites and YouTube channel.