In this episode, we host Korkut Akın, a versatile artist who blends cinema, television, writing, and education. Akın invites us to an intimate conversation spanning his 44-year tradition of handcrafted New Year’s cards to his experiences in cinema and television, along with his profound perspective on art and society.

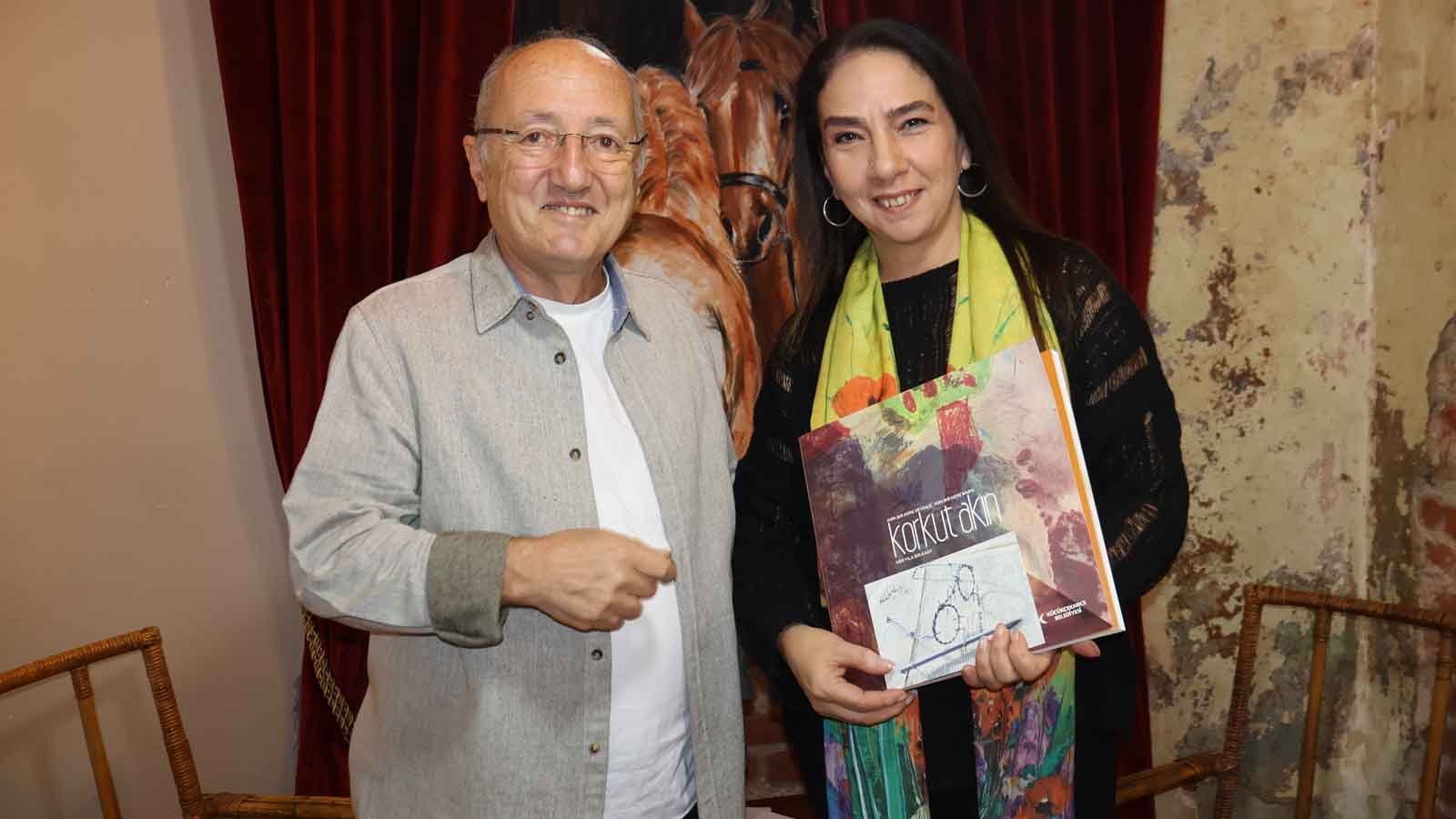

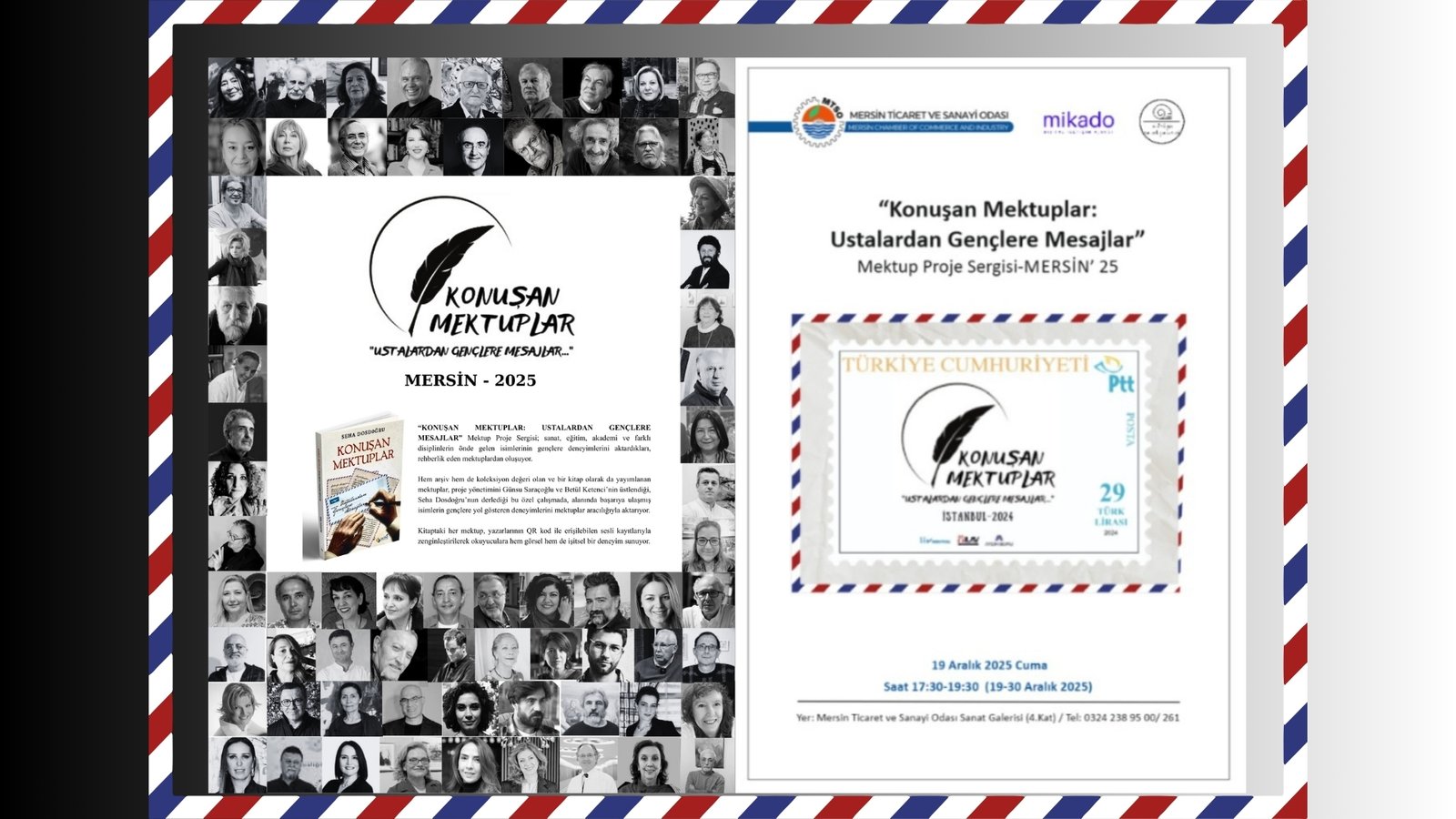

Korkut Akın recounts the tradition of his New Year’s cards, which began in 1983 as a gift for a friend made from a negative film strip and has continued each year with a special theme. The cards are never sent by mail; they are only distributed face-to-face, by hand. This is part of Akın’s emphasis on the importance of in-person communication. This special collection was crowned with a book titled “Korkut Akın’dan Yeni Yıl: 1983-2023 Kartpostallar Kitabı” (New Year from Korkut Akın: 1983-2023 Postcards Book). The postcards aim to keep alive the personal touch and sincerity that are fading in the increasingly digitalized world.

Akın’s interest in cinema began in childhood with a primitive projection device he made from a margarine box and a magnifying glass. He belongs to the first generation to receive formal cinema-TV education. After graduation, he started working in the press sector (Hürriyet) to break into Yeşilçam (the Turkish film industry). His short films won awards at national and international festivals (“Voli”, “Sait Faik’ten Hişt Hişt”, “Hayat Ne Tatlı”). He defines the short film as an art of “conveying a lot with a little” and transmitting emotions through imagery.

Akın emphasizes that in literary adaptations, it is neither possible nor necessary to convey every detail from the book. He argues that the primary function of cinema, and art in general, is not to “deliver a message” but to “create an emotion.” This emotion should allow the viewer/reader to find their own interpretation and path. As an example, he points out that Ahmet Arif’s poem “Hasretinden Prangalar Eskittim” was actually written as a love poem, but listeners interpreted it differently based on their own political sentiments.

He sees cultural-art programming on television (such as İstanbul Sayfaları) as an important tool for popularizing this field and integrating it into daily life. He believes that a society where culture and art are strong is more resilient and capable of collective action against all kinds of difficulties.

He criticizes the current rapid production process for TV series and films. He thinks that not allowing sufficient preparation and internalization time for scripts, actors, and crews lowers quality. He states that excessive working hours and disorganization on sets are at the root of the problems.

From his educator perspective, his most important advice to young filmmakers is to “read.” He emphasizes that filmmakers should engage in broad reading and that it’s important not just to look but to truly see. To explain different perspectives to his students, he uses the example of the hidden writings on his New Year’s cards.

At the end of the program, he says that the thing he is most glad to have done is his 44-year postcard tradition, and he expresses his wish to continue it. He bids farewell to the viewers with wishes for peace, democracy, and an organized life.