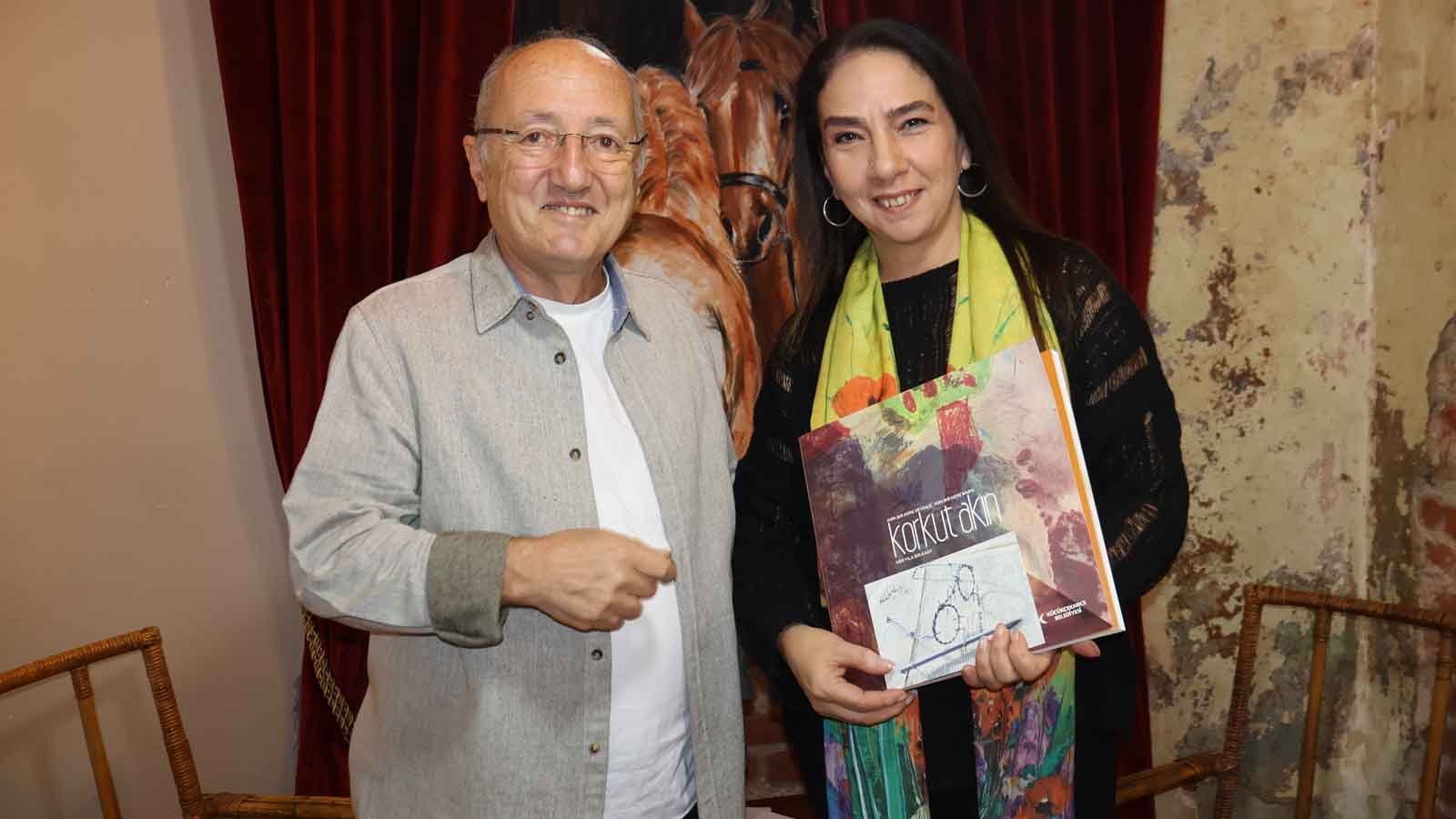

Teacher of the Deaf, author and women’s rights advocate Sibel Süslü shared the journey that stretches from the childhood dreams she whispered to the stars while growing up among sheep in a village, through her battle with body image, to the quiet-language stories she writes and the solidarity she builds among women, as the guest of Eylül Aşkın in episode 114.

Recorded at Nostalji Antik in Cihangir, Istanbul, the 114th installment of “Özel Söyleşi with Eylül Aşkın” stands out with author Sibel Süslü’s heartfelt narrative. Born in 1993, Süslü recounts a path that began with the first dreams confided to the stars while growing up in a village of Alaşehir, Manisa, and reached the human stories she later observed on the streets of Kadıköy. Lying under a vine arbor as a child and locking eyes with the Eagle constellation became the first sparks of her passion for writing; the books she read aloud to the sheep initiated her habit of turning her inner world into words.

After graduating from the Department of Teaching the Hearing-Impaired at Istanbul University, Süslü has worked in special education for more than a decade. Experiencing the power of communication built in a silent language, she simplified her written style and learned to establish deep empathy. The bond she formed with the hearing-impaired mother of one of her students—through eye contact, facial expressions and emotions—reinforced her belief that “when words are absent, the body speaks.” This experience became a pivotal moment that nourishes both her teaching and her writing.

Her first book, “Zamansız” (“Timeless”), published in 2023, is a three-part diary written for the beloved she lost to a sudden heart attack at the age of twenty-seven: “What We Lived,” “After You,” and “Immortalized.” Süslü says the journals she kept gradually turned into a record and a means of immortalization. The birth of the book encompasses both her personal grieving process and her observations on the female body, emotions and social roles. “Some memories refuse to fit into a timeline; I wanted to freeze them in writing so I would not forget, yet be able to return to that moment whenever I reread them,” she explains.

Süslü also openly describes how her body, which reached 48 kilos during university, was turned into a “self-worth prison” under social pressure. She conveys, with concrete examples, the psychological dynamics behind her weight-loss process, the stereotypical beauty norms surrounding women’s bodies, and the damage these norms inflict on the mind. “Judgments made about women’s bodies imprison us in cells we build for ourselves. I tore those walls down; now I reach a hand out to other women,” she states—an idea that forms the backbone of her forthcoming essay collection.

Street observations in Kadıköy provide rich material for her writing. The difference between empty balconies and those adorned with flowers, the rosy-cheeked street vendors, elderly men walking with canes—all find their place in her narrative web. “While watching people I construct life scenarios for them in my head; these tiny details both feed me and seep into my writing,” she says. The tension between the very different characters she sees in central Kadıköy and the quiet residential pockets of Erenköy allows her to grasp both human psychology and the impact of urban transformation on the individual.

Three new works will meet readers in 2026. In February, the collective poetry chapbook “Yürekten Dökülenler” (“Spilled from the Heart”), prepared with friends, will hit the shelves. Mid-year will see the release of “Kadın Formları” (“Female Forms”), a collection of essays exploring the diverse life patterns of women. In the fall, the illustrated story “Kalbini Bekleyen Çocuk” (“The Child Waiting for a Heart”), narrated through the eyes of a child awaiting heart surgery whom she met in hospital corridors, will address young readers. With each of these three works Süslü aims to amplify the voices of women, children and silent individuals labeled as “the other.”

The author views Turkey’s declining reading rates and the way digital platforms erode children’s reasoning abilities with great concern. “A generation is growing up that touches tablets but never holds a pencil. Children who cannot write compositions or form their own sentences cannot find their own voices either. Writing is as important as reading; to hear your own voice you must first put it on paper,” she says. Drawing on her experience as a special-education teacher, Süslü continues to convey the healing power of writing to both her students and adult readers.